SIBs: What's in a name?

Posted:

7 Nov 2019, 7 a.m.

Authors:

-

Nigel Ball

Former Executive Director, Government Outcomes Lab

Nigel Ball

Former Executive Director, Government Outcomes Lab

-

Andreea Anastasiu

Executive Director, Government Outcomes Lab

Andreea Anastasiu

Executive Director, Government Outcomes Lab

Topics:

Impact bonds, Outcomes-based approachesIn this piece, GO Lab’s Nigel Ball and Andreea Anastasiu reflect on some of the key recommendations of a recent study into the challenges and benefits of commissioning social impact bonds in the UK, and the potential for replication and scaling.

As we have pointed out before, the use of the impact bond tool in the UK has not grown at the rate that many predicted and hoped. The UK government recently commissioned research to investigate the potential for scale-up of the model, which was published on 4th November 2019. For those who remain curious about the relative benefits and costs of the model, the report offers some interesting insights. The authors of the report, Ecorys & ATQ, summarise the main findings of the report in their own blog here. We give our own reflections below.

Scaling what?

Impact bonds are not an on-the-ground intervention, they are a form of funding and contracting. In looking at “routes to replication”, the report does not always disentangle the two. In those rare cases where it is possible to test, standardise and scale-up an intervention, it might be that funding it through an impact bond enhances delivery. A recent evaluation makes such a claim, but we still do not know if this is enough to justify the additional cost and complication an impact bond brings. It could be more useful to look at impact bonds as a tool of system change – to align interests between multiple agencies or organisations, shift spend upstream, or increase the focus on ongoing learning and refinement – the “collaboration, prevention and innovation” we identified in our 2018 “Building the Tools” report.

What's in a name?

The report re-surfaces an old discussion about why impact bonds are so named, given they are not bonds. Some new adopters of these approaches are already employing alternative terminology such as “social impact partnerships” and "social outcomes contracts". But others argue that these alternative names do not properly distinguish key features that make impact bonds distinct from a wider family of contracting mechanisms – for example, the unique involvement of third-party social investors, or the focus on narrow local service footprints.

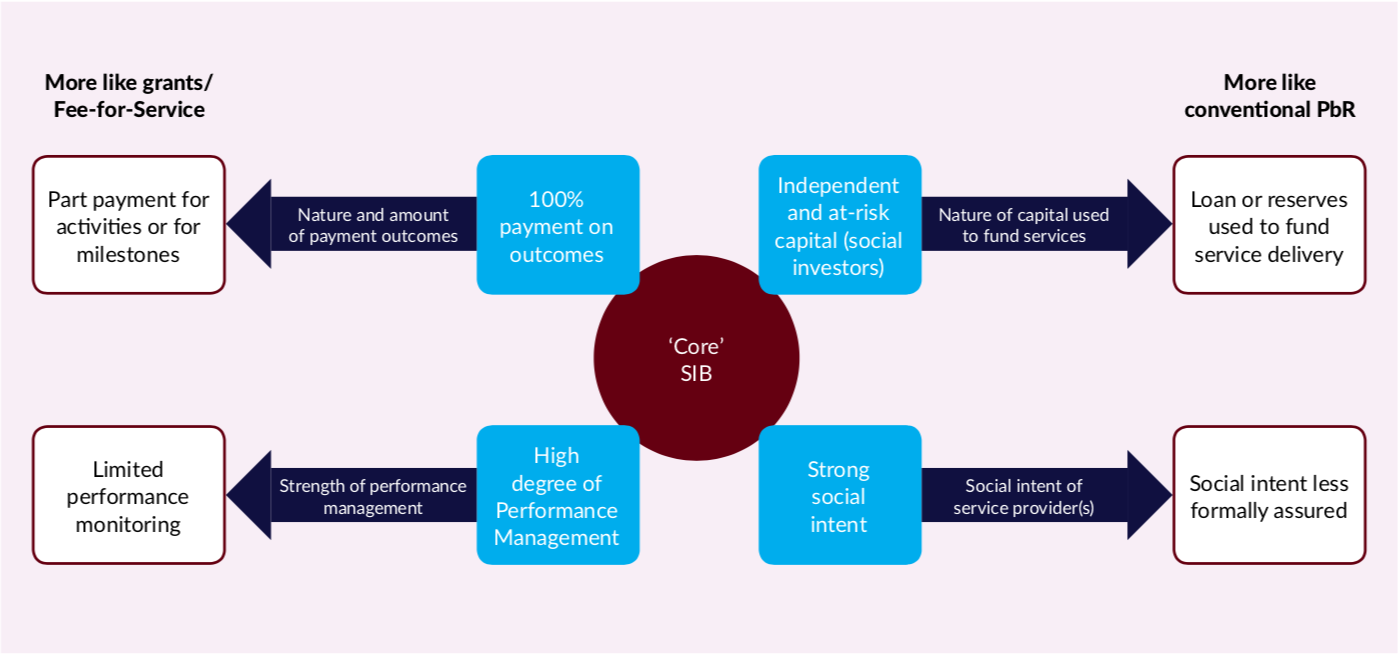

That points to a more fundamental issue than simply the name we use. The real issue here is that projects which are referred to as “impact bonds” vary to such an extent that it is practically impossible to write a definition that applies to all of them (though we have tried). In “Building the Tools”, we identified four dimensions along which these projects differ: how strongly they rely on payment for outcomes rather than inputs; what sort of up-front capital they use; how socially-oriented the partners are; and how actively performance management is used.

The report is right to point out that the association with a financial instrument still makes impact bonds look like they are just an “invest to save” accounting trick, with limited utility in changing how things work on the ground. In reality, as mentioned earlier, we have often seen impact bonds applied as a tool of system change. The moulding of the model to fit a wide array of apparent service problems is a symptom of how hard it is to meaningfully effect systems change on the ground. But this fluid application of impact bonds can be hard to square with the quest for replication, which relies on at least some degree of standardisation. Perhaps we should start to ask whether some distinct impact bond typologies might be distilled from the existing practice - and then we can decide what to call them.

Transparency

Of course, to scale up impact bonds, it would be helpful to have more detail on the existing projects, and the report is right to point out the lack of availability of data. Information on the price of outcomes, performance, and projected investor returns of previous projects is clearly going to be important. Currently, this is often the most difficult information to get access to.

The report mainly encourages voluntary sharing, but project stakeholders might think of plenty of reasons not to do so. France’s approach of creating a joint ethics statement that key stakeholders can sign up to might provide some inspiration – but to create a genuine shift, government agencies need to mandate publication of data. Many US state and local governments publish their contracts, which means that the contracts can be compiled, analysed, and used as templates by other state and local governments. For example, the Nonprofit Finance Fund, a US organisation, provides 11 different pay-for-success contract documents from different state and local governments as samples. At the GO Lab, we are creating a global database to hold project level information for the benefit of those seeking to learn from the implementation of the model.

Commissioner capacity-building and peer support

The report points out the breadth of technical information available on the various aspects of developing impact bonds – much of it hosted by us at the GO Lab. We are keen to use this knowledge to unlock insights that can be applied to wider practice – such as how to decide how much to spend towards efforts for better outcomes, or how to use procurement regulations more creatively. We would love to work with relevant professional organisations such as the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) and the Crown Commercial Service in the UK, and the Centre for Global Development and the World Bank worldwide, to disseminate this. The starting point should be identifying a public service challenge that needs to be addressed, rather than promoting the use of impact bonds for their own sake.

But again, publishing technical information obscures a deeper challenge: identifying and developing the skillset that those working in public sector organisations need in order to help secure better outcomes for people. This extends far beyond the technical realm. We should be asking, for example, what kind of organisation culture do we need to foster within contracting authorities?

One way to develop these sorts of skills is through peer learning. In accord with the report, we have seen a great demand for this type of support: commissioners are keen to learn from one another. Indeed, the GO Lab has been working with partners in the UK government, The National Lottery Community Fund, and Ecorys to support the set-up of local “knowledge clubs” in the UK.

The report also revisits the idea of development funding, which has been used in the UK to help impact bond projects get off the ground. Such funding has clearly been critical. But much of it flowed to consultants. Does it leave a lasting impact on the capacity of those working in public service to develop their own innovative approaches? Secondments of experienced practitioners into commissioning authorities, as the report suggests, might be a more effective way to seed knowledge within organisations.

Should we be scaling up at all?

Some might challenge the underlying assumption that impact bonds are worth scaling up at all. Even despite the scarcity of information on project performance, few would deny that the tool presents a mixed picture of success. Rather than becoming mainstream, it could be that their main role is to nudge the status quo into change. Perhaps they will remain “challenger” projects which inform wider practice in cross-sector working, procurement, impact measurement, and a multitude of other areas. As we have argued elsewhere, in a world full of stubborn social challenges, and with no straightforward answers on how to tackle them, that could be valuable in its own right.