How to write the rules for payment in PbR, SIB and other outcomes contracts

The idea of an outcome-based contract (like the kind you get in social impact bonds and some other types of payment-by-results) has a deceptive simplicity: a government agency pays only when they see evidence of the change they are looking for in the lives of citizens. The reality, of course, is not simple at all. Anyone who has attempted to commission, deliver or invest in a contract like this knows that setting it up effectively is fraught with challenges.

From an outcomes-based contract to work, there needs to be a set of rules written down, explaining when and what evidence needs to be provided for the government agency to pay. Collectively, these rules are often referred to as a 'payment mechanism'. Payment mechanism may not consist entirely of payment for outcomes - these are sometimes only used to pay part of the total contract sum, with the rest either being for delivering a specified service (as in the more traditional approach) or for evidencing particular outputs (eg.showing people engaging with the service, or completing a course).

At the GO Lab, we are still working to understand the many different approaches to writing these rules, and the effects that these contrasting approaches have - both on the day-to-day delivery of projects, and the eventual outcomes achieved for citizens. We are planning to produce some detailed technical guidance on the topic in due course, laying out several examples and the pros and cons of each.

Payment by results in a sentence

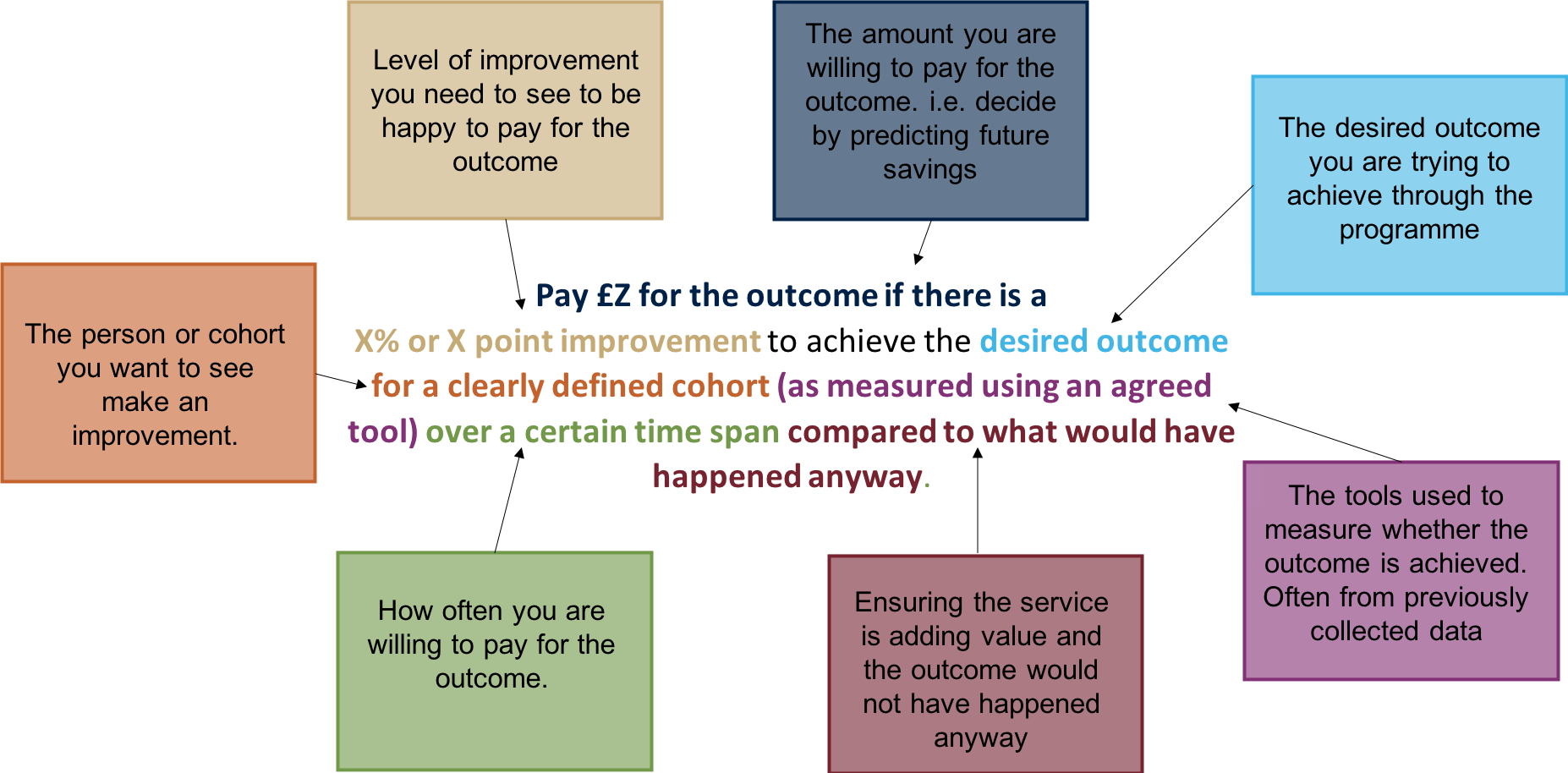

In the diagram below, we show that a written rule for payment for an outcome can be expressed in a single sentence, as long as that sentence contains seven key elements. The brevity is deceptive - a phenomenal amount of work often goes into getting each of these seven elements right. And remember that most payment mechanisms have more than one rule for payment - you may want to be paid over the course of a contract. If that is the case, several of these 'written rule' sentences are likely to be needed!

After the explainer we've provided a couple of real-life examples to illustrate how this might look in practice.

To explain in this image of the payment by Results in a sentence, here is a more in depth illustration of each of the seven elements.

Pay £X amount for outcome - is the amount you are willing to pay for the outcome. You can decide this is in a variety of ways - mostly it is either done by predicting future savings, or looking at the cost of the service (or a comparable service). The thing you need to watch out for is that a provider needs to estimate how many outcomes they think they might achieve under an outcomes contract, and therefore how much they'll need to be paid. If this isn't enough to cover the cost of running the contract, they won't do it.

Level of improvement - this is the amount of change you want to see before you are happy to make the payment of outcome. It needs to be challenging but achievable. You will need some sort of prior evidence to guide where to set this level, and you need to set it in dialogue with providers/investors. They might have a very different idea of what is achievable to you!

Desired Outcome - this is what you are trying to achieve from the programme.

Who is the programme aiming to support? - The outcome could be referring to an individual or a whole cohort. Either way, you need to describe this in a way that ensures providers work with all people and not just the easiest to engage. That may mean describing in some detail the eligibility for someone to be part of the cohort.

Measurement of outcome - this is the selection (and sometimes also collection) of data you will use to measure whether the outcome has been achieved. The data needs to provide a reliable and valid measurement of the outcome. In selecting data, you may be able to use data that is already collected by someone (often called 'administrative data'), for example academic performance in school. Or you may want to collect new data - in which case you should look for an existing, standardised assessment tool rather than making up your own way of measuring something - for example, the Warwick Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS), often used by the NHS to measure mental wellbeing.

Timing - is how often you are willing to pay for the outcome. It could be a one-off event (e.g. a school pupil is not excluded from secondary school, which is then paid when they finish their GCSE exams), or it could be more frequent (e.g. each day of social care avoided by a child at risk of being taken into care, which could be aggregated into a quarterly payment to reduce the administrative burden).

Ensuring value is added - is the evaluation element of the metric. Including this is a way of checking that the outcome is above and beyond what would happen anyway, even if the service wasn't delivered (known by economists as a 'deadweight'). This can be tricky to do in practice. The 'gold standard' is a randomised controlled trial, or RTC, an approach adapted from medical research. The most basic method would be to estimate what might happen anyway, and only pay for outcomes above and beyond this level.

Putting this sentence into practice

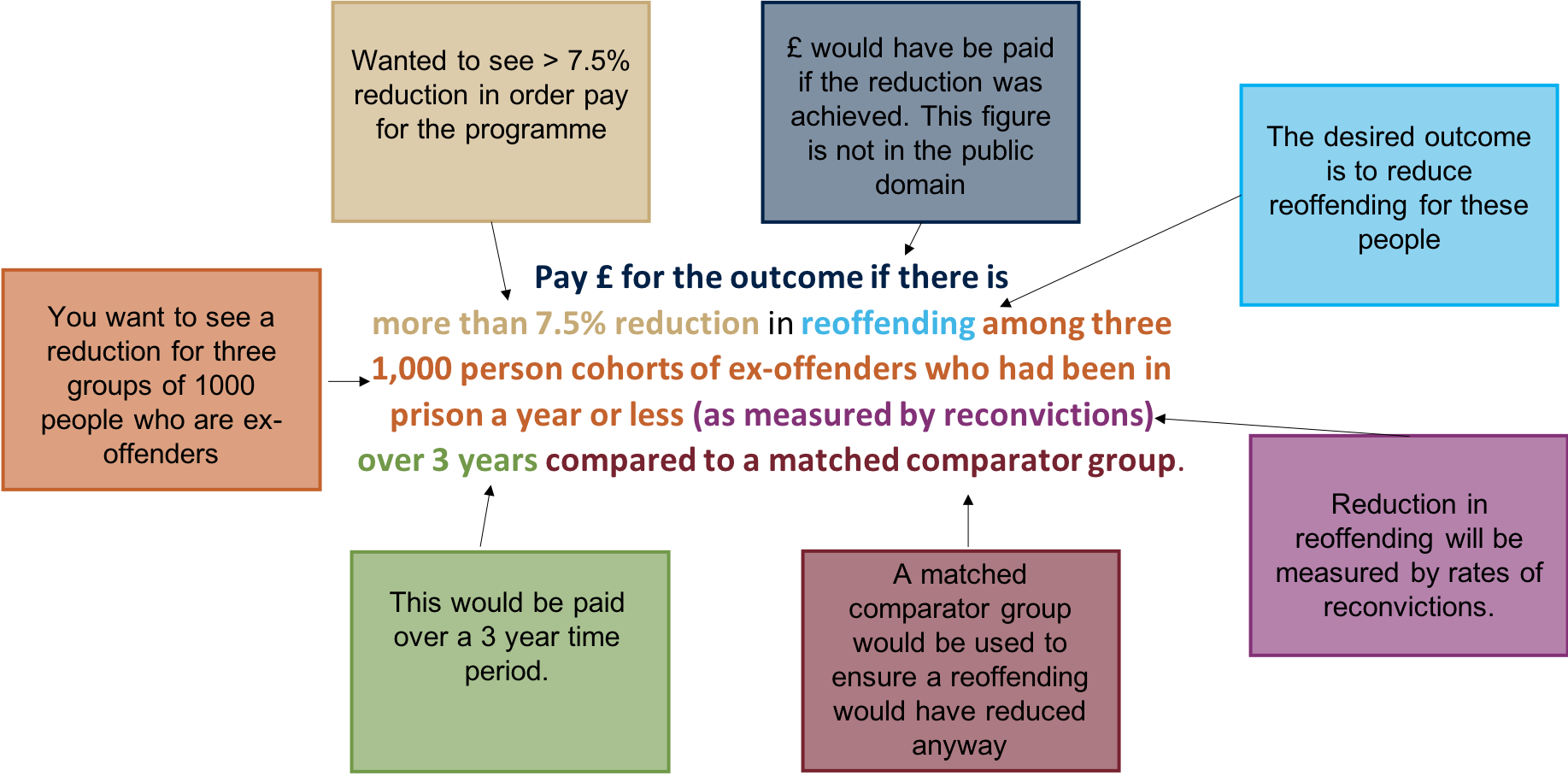

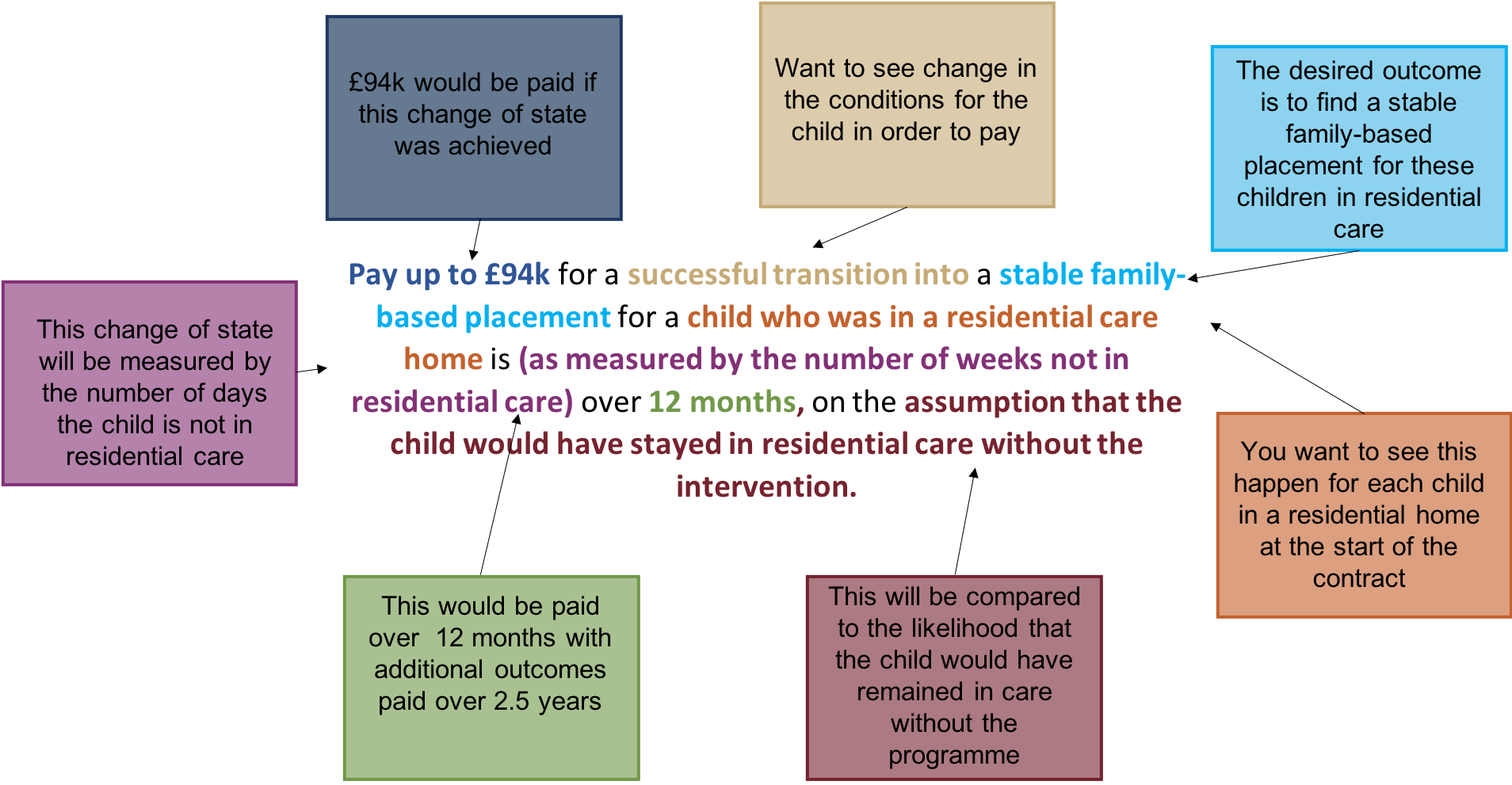

To illustrate how this works in reality, here are two examples of the payment by results sentence

Peterborough Social Impact Bond

Manchester Treatment Foster Care (MTFC)

If you're finding this difficult - don't despair. Writing the payment rules is probably the hardest bit of setting up an outcomes contract. We hope that the above helps. Remember the GO Lab is available for Advice Surgeries every Tuesday morning - we will be happy to help you think things through if you get stuck.

This blog piece has been written by the GO Lab team and Catherine Remfry, Economic Advisor at the Centre for Social Impact Bonds at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Thanks for your contributions Cat!